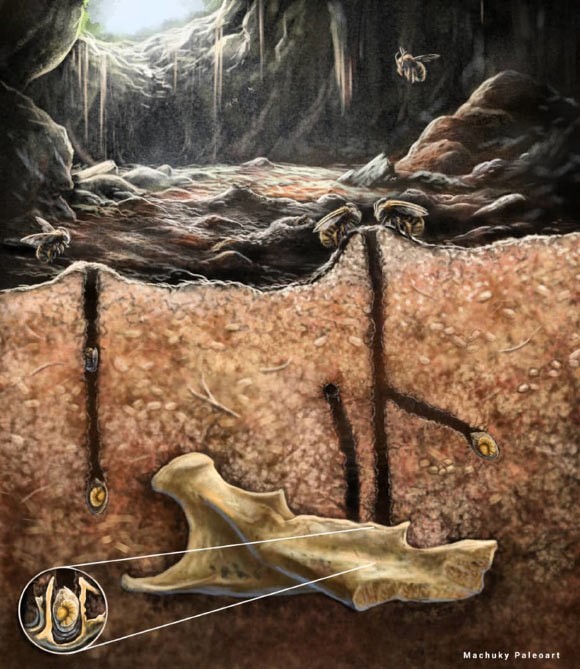

Paleontologists have unearthed the first known instance of ancient bees nesting inside the fossilized remains of vertebrates. This remarkable discovery, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, sheds light on the adaptability and surprising behaviors of these insects over millennia. The trace fossils were found in a Late Quaternary cave deposit on the island of Hispaniola, revealing that bees constructed individual brood cells within the cavities of animal bones.

A Unique Nesting Strategy

The study, led by Field Museum paleontologist Lázaro Viñola López, details the discovery of structures named Osnidum almontei – smooth, concave sediment formations within the empty tooth sockets of fossilized mammal jaws. These formations weren’t random accumulations of dirt; they matched the shape and structure of mud nests created by some bee species today, and even contained ancient pollen grains – food left for developing larvae.

Researchers utilized CT scanning to examine the fossils without damaging them, confirming that the sediment structures were deliberately built by bees. These tiny nests, smaller than a pencil eraser, appear to have been constructed using a mixture of saliva and dirt.

Why Nest in Bones?

The researchers hypothesize that this unusual behavior arose from a combination of environmental factors. The limestone terrain in this region lacks extensive soil cover, potentially forcing bees to seek alternative nesting sites. The cave itself served as a multi-generational home for owls, who deposited countless bones through regurgitated pellets – providing a readily available supply of pre-made nesting cavities.

The bones likely offered protection from predators, such as wasps, that might otherwise target bee larvae. This behavior is especially notable because most bee species are solitary, laying eggs in small cavities rather than constructing large colonies like honeybees or paper wasps.

Implications and Future Research

The exact species of bee responsible for these nests remains unknown, as no preserved bee bodies were found. However, the unique nest structures have been classified as Osnidum almontei, named after the scientist who first discovered the cave.

The discovery underscores how little we still understand about bee ecology, particularly in understudied regions like Caribbean islands. It also highlights the importance of careful fossil analysis: what may appear as natural sediment accumulation could be evidence of ancient behavioral adaptations.

“This discovery shows how weird bees can be – they can surprise you. But it also shows that when you’re looking at fossils, you have to be very careful,” Dr. Viñola López stated.

This research challenges our assumptions about insect behavior and demonstrates the resourcefulness of bees in exploiting unconventional nesting opportunities. The findings further emphasize the value of paleontological research in revealing the hidden histories of life on Earth.